Soham De, Anmol Panda, Joyojeet Pal

We examined the social media messaging related to the Hijab Ban, starting Jan 31, 2021, and ending on Feb 20, 2022. The goal of this work was to examine both the frequency and importance of the messaging and understand the key actors who took part in it, the ways in which they shape the discourse.

Key players

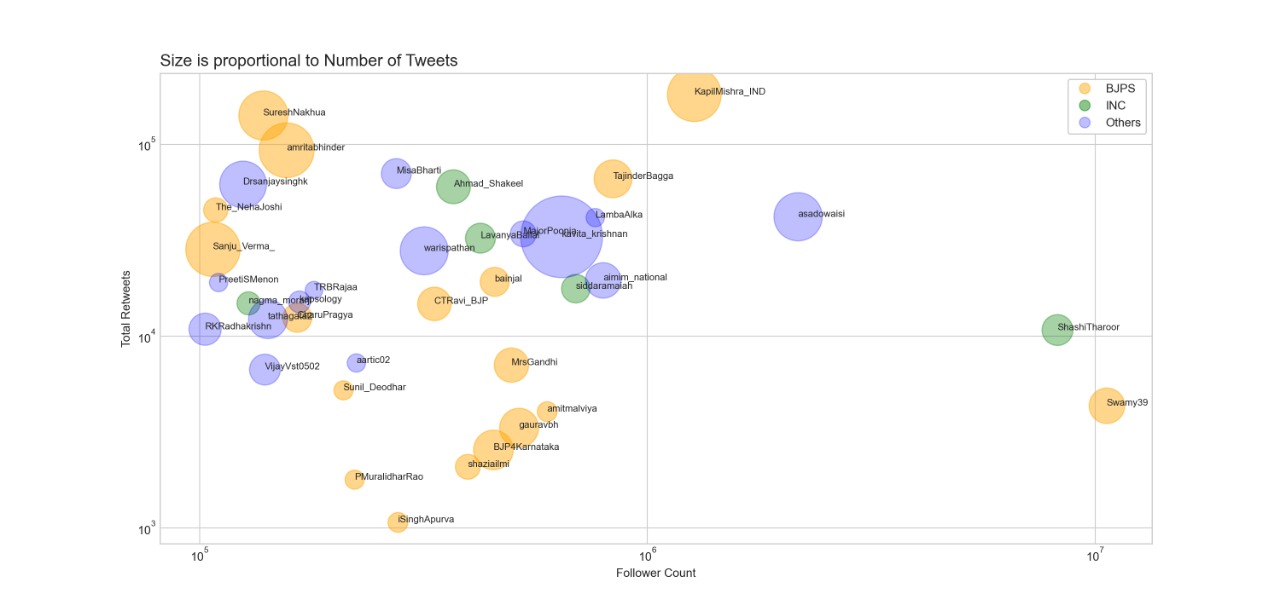

First, we look at the key players, in terms of the overall impact they have through their engagement on the issue of the Hijab ban. We see first that there are more highly-followed influencers who are in favour of the ban, (or opposed to wearing Hijab in schools) than there opposed to it. Specifically, BJP-supporting influencer Anshul Saxena and Surendra Poonia, BJP politician Kapil Mishra, and right-leaning anchors Rahul Shivashankar and Suresh Chavankhe had the most engagement on their messaging critical of wearing Hijab in schools.

We also see that the overwhelming majority of high-influence Twitter accounts with an opinion on whether or not women should wear Hijab are male.

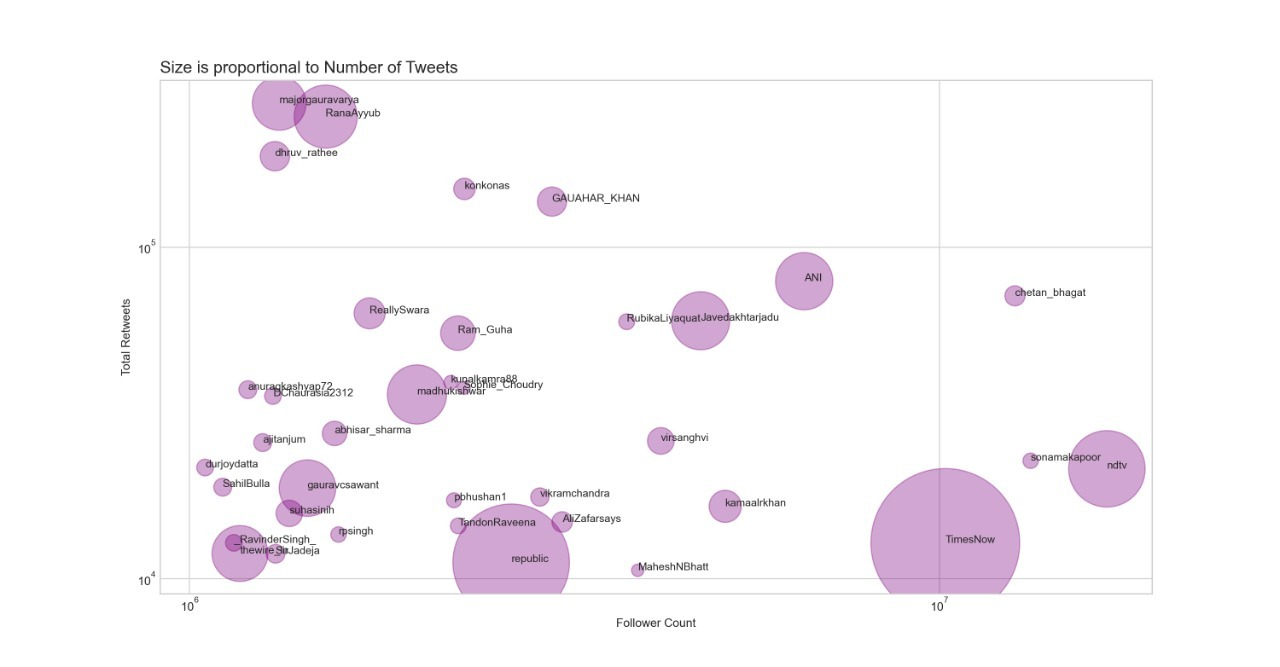

Fig 1: Visualizing Users with the top-200 most RTed Tweets on #HijabBan

Size of each bubble is proportional to the total number of RTs the user has accumulated on their tweets about Hijab in the top-200. Key observation here is the majority of pro #HijabBan users at the highest end of the most-RTed content. We only visualize highly influential accounts (followers > 104) with at least 2 tweets in the top-200 RTed tweets

On the side opposed to the Hijab ban, we find that the most engaged influencer was academic Ashok Swain, followed by factchecker Mohammed Zubair. Journalists Ashraf Hussain and Imran Khan were among the most engaged from among commentators. When we look at the scale of the engagements, a few other interesting patterns appear. We also see a pattern comparable to elsewhere in the world, where highly polarized news sources that do not operate on traditional media – such as @MeghUpdates @JantaKaReporter become a key source of partisan information during a highly volatile event.

Fig 1a: Extended list of influencers and news sources

Fig 1b: Extended list of politicians

Scale

The first pattern we see is that the number of anti-Hijab ban are far more numerous, but that the pro-Hijab ban tweets tended to be sent by a smaller number, but highly engaged accounts. This suggests that the overall sentiment is opposed to a Hijab ban, but that a vocal minority with a significant online reach is able to build a significant online footprint.

We observe that the highest tweeting activity on the #HijabBan topic was concentrated on 3 days (7th – 9th February). Each of these days has a time-interval of a few hours (typically, around 7:30 PM IST) which attracts the largest volumes of tweets on the issue. Tweets on each of these three days also seem to focus on a new argument to support their respective side on the debate. In the case of anti-ban tweets, the core argument evolves from Hijab being an individual right to that of Education being a right. On the other hand core pro-ban arguments stress on the importance of uniform over Hijab and almost always have a religious undertone

Fig 2: Timeline of Hashtag frequencies from Jan 31st to Feb 20th (plotted hourly)

We annotated 5 major points when Twitter activity increased.

1: Feb 5, the BB Hegde and Bhandarkar college incidents caused trending, Rahul Gandhi tweets about issue

2.Feb 7 #HijabIsIndividualRight starts trending, counter protests increase, #YesToUniform_NoToHijab starts trending on pro-ban side

3. Feb 8, Muskan Khan incident trends, major global accounts incl Malala Yousafzai and John Cusack tweet on the issue. #JaiShriRam starts trending on the pro-ban side. Tweets about court proceedings start trending.

4. Feb 9, #EducationIsMyRight starts trending alongside #HijabNahiKitaabDo on the pro-ban side, several pro-ban influencers tweet in succession, presenting Niqab as equivalent to Hijab

5.Feb 11, US International Religious Freedom Ambassador tweets in opposition to Hijab ban, triggers pro-ban activity, mostly focused on cases of Muslim women who chose not to wear Hijab and were attacked or trolled

We sampled the highly engaged messages, and went through the top 200 most retweeted messages, and found that

- Almost 70% of the top 200 RTed tweets that took a position (58 out of 86) are pro-ban. This suggests a high degree of mobilization was done through a smaller number of tweets. This is a typical pattern seen in cases of astroturfing.

- This is confirmed by the fact that from the total number of tweets that took a position, anti-ban tweets are about 500% more in volume than pro-ban tweets (63582 vs 12649). Even further evidence is seen in the fact that anti-ban tweets have a 360% retweet rate of the pro-ban tweets. The Pro-ban tweets had a mean retweet rate of 1.445, Std Dev: 98.45889070618168 (#12649), whereas the anti-ban tweets had a mean RT: 5.327, Std Dev: 61.38868951553676 (#63582)

- In summary, these suggest that a far higher proportion of people engaging content on Twitter oppose the Hijab Ban, but that a small number of highly-networked influencers are driving the counter side of the debate.

Division

We plotted the last three accounts retweeted by accounts that tweeted clearly pro- and clearly anti-Hijab ban. We see two clear patterns. On the anti-Hijab ban side, the majority of voices are from accounts that retweet leading Indian Muslim voices on Twitter. These include organizations that have mobilized around the Hijab ban including Popular Front of India, the Students Islamic Organization of India, the student wing of Jamaat-e-Islami emerge as key handles, as do Asad Owaisi, and factchecker Mohammed Zubair. The issue has also brought to the forefront a number of new faces — these include influencers who shed light on Muslim issues – including Mohd Abdul Sattar, Raza Khan, organizations like Roshan Mustaqbil. The spread of journalists whose work gains attention also highlights people who have focused on, or done ground coverage of the Hijab ban issue including Ashraf Hussain and Rushda Khan.

Fig 3: Word clouds sized by frequency of Twitter Accounts most retweeted by accounts opposed to the ban (L) and those in favour of the ban (R)

The accounts were arrived at based on the three accounts most frequently retweeted by any account in the last 6 months, from those also tweeting positively or negatively about the Hijab ban issue.

The most co-retweeted on the pro-Ban side has some a mix of popular BJP leaders, including Modi, Yogi, Amit Shah and JP Nadda. But we also see a key account – HinduJagrutiOrg, which is frequently retweeted by the same accounts that post a lot of pro-ban material. We see influencers who are typically popular with the right, including Anshul Saxena and Surendra Poonia, but also includes some accounts that consistently post hateful visual content including @alphatoonist and @incognito_qfs, underlining the radicalization of the pro-ban side.

Two interesting patterns emerge here. First, that the side that rallies online against the ban largely relies on influencers from within the Muslim community. Unlike in previous events like the CAA, in which the spread of social media activity included a number of influencers engaging on behalf of Muslims being targeted, and in turn, being engaged by Muslims on Twitter, we see a much greater concentration within the community of Muslims in case of the Hijab ban.

Fig 4: (Below) Activity of general Twitter users. We see in this figure, in which each dot is a single account tweeting for or against the Hijab ban, that the vast majority of dots are yellow, in that the overall activity against a ban far exceeds the activity in favour of a ban. But we also see that there are more individual accounts that have a smaller number of tweets with low engagement on the anti-ban side.

Thematic Buckets in Individual tweets

We see some consistent patterns in the tweeting about the Hijab ban issue, particularly those tweets that went highly viral. We break these into a few broad categories to help make sense of what has driven the discourse over the last month.

Political Posturing

First, we see a small number of politicians’ tweeting about the issue – the only national party whose two top leaders, engaged the subject publicly on the side of those protesting the Hijab ban was the INC – both Rahul and Priyanka tweeted about it. However, political tweets also put forth a political agenda. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra’s tweet on the issue was the single most engaged message, but it included a shout-out to the party’s Uttar Pradesh slogan, #LadkiHoonLadSaktiHoon.

On the other hand, from the BJP side, the posturing was more aligned with the othering of Muslims. Interestingly, no major leaders from the party tweeted about the issue, leaders with Twitter cache but political insignificance such as Subramanian Swamy and Kapil Mishra were among the few to engage in pro Hijab-ban messaging.

While AIMIM took a direct stance defending the right to Hijab, other parties that rely on secular posturing including Samajwadi Party, Trinamool Congress, and Nationalist Congress Party were all silent on the issue.

Whataboutery

A trend that is fairly typical during polarized online events is the use of whataboutery, where instead of focusing on the issue at hand, the goal is to deflect. This was done here by presenting arguments of minority rights in Afghanistan and Pakistan, or individual cases of deaths of Hindu persons. A case in point was from BJP IT Cell member Shezad Poonawala.

Separating out Hijab from other religious markers

The argument that the exclusion of Hijab from other religious markers, particularly Sikh Turbans, has been a consistent argument of the pro-Hijab ban. While this could be seen through the prism of avoiding alienating Sikhs, particularly in the middle of a state election, it could also be argued that the general stance is just to other Muslims.

NIMBY-ism

While messaging from Malala Yousafzai, Paul Pogba, John Cusack, and eventually the US Ambassador on International Religious Freedom, all added to the calls against a Hijab ban, a number of Indian influencers came in with some form of “stay out of our affairs” or whataboutery.

Existential Risk

Finally, we see repeated elements of existential risk in the way the issue is presented as an existential threat to Hindu ways of life. Messages in this vein do not hint at whataboutery, but instead present Hijab as a tip of an iceberg that will eventually usurp India culturally.

Methodology

Data Collection

From January 25th to February 12th, 2022, we collected all tweets on Twitter containing the word ‘Hijab’. Each tweet object has associated fields of which the text, mentions, hashtags and public metrics are of particular interest to this study.

Hashtag Frequency and Categorisation

Each tweet collected may have associated hashtags. We collect all these hashtags and inspect the most frequently used ones. Of them, we created the following subsets:

- Against #HijabBan: ‘HijabisOurRight’,’HijabIsFundamentalRight’,’HijabIsIndividualRight’,’EducationMyRight’,’हिजाब_से_दर्द_क्यों’

- In support of #HijabBan: ‘HijabNahiKitaabDo’,’Hindutva’,’saffronshawls’,’YesToUniform_NoToHijab’,’JaiShriRam’,’Pakistan’,’BanHijab’

We intentionally omit certain hashtags like #HijabRow, #Hijab and #HijabBan as despite being the top-3 most frequently used tags, these were used in tweets on both sides of the debate. Here is a link to a full set.

Argument Extraction

To extract and analyze semantics of the core arguments used on either side of the debate, we consider the top 1000 tweets on either side of the debate. As a preprocessing step, we use a Fuzzy Search algorithm to remove multiple occurrences of similar tweets (tweets with a fuzz ratio of over 0.85). We then embed these tweets onto a 512-dimensional vector space, using a modified version of Google’s Multilingual Universal Sentence Encoder (mUSE). To visualize the embeddings and remove redundant information, we reduce the dimension of the vector embeddings to 2-dimensions using UMAP.

Finally, on the reduced vector space, we use Hierarchical Clustering (HDBSCAN) to extract the main clusters. Experimentally, we set the minimum size of each cluster to be 20. We then manually inspect tweets from each cluster to assign a particular common argument to each of them.